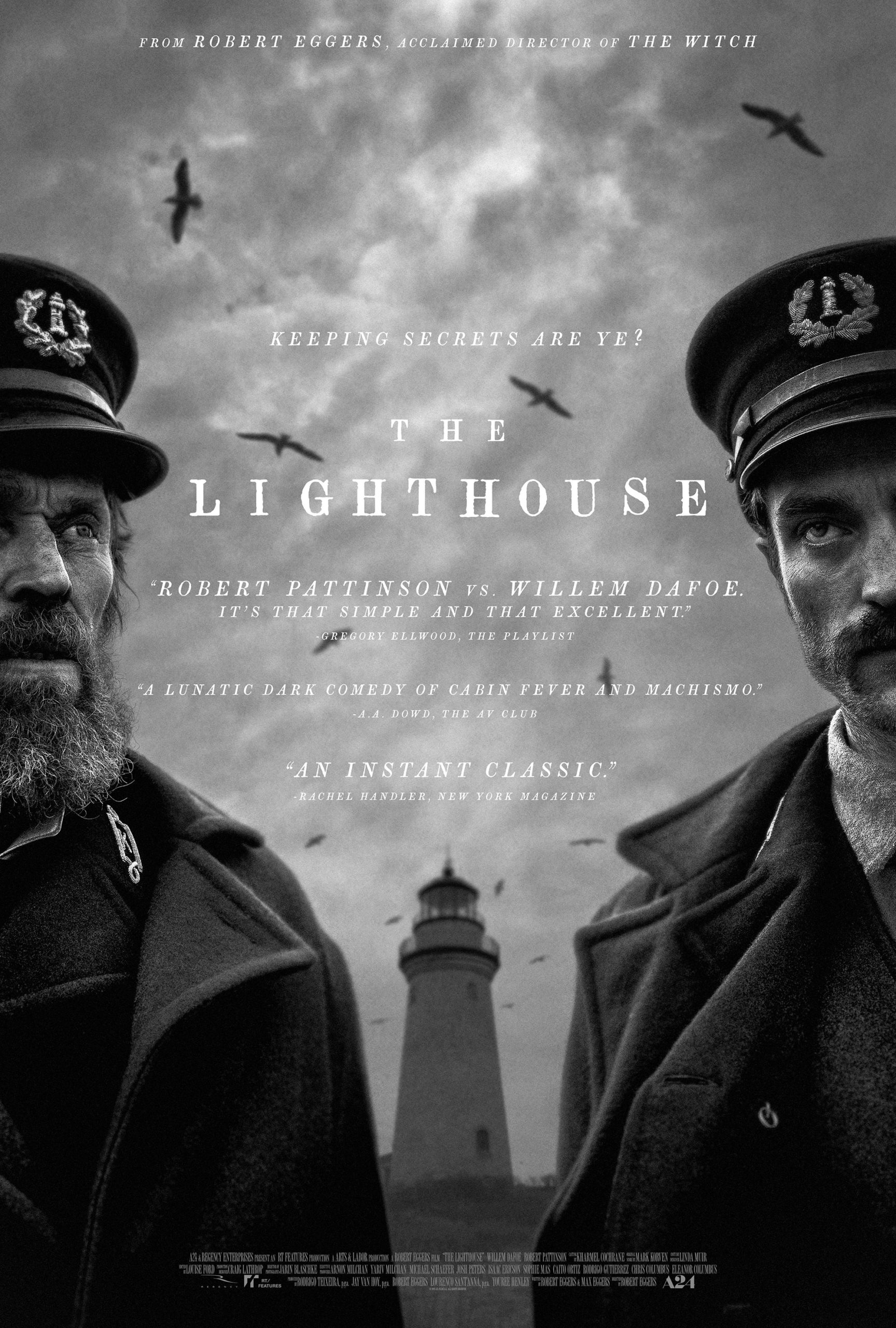

Movie poster of “The Lighthouse.” A24

By Eva Bryner

Fantasy and horror are seamlessly intertwined in Robert Eggers’ new film, “The Lighthouse.”

The film follows Thomas and Ephraim, two rough, pipe-smoking, sea hearty men played by Willam Defoe and Robert Pattinson respectively, as they take an Olympic-style high dive into brutal isolation.

Ephraim, played by Pattinson, is a young quiet man who shows up on a barren island to be the new second-in-command for Thomas, the salty ex-captain turned lighthouse keeper, played by Defoe. The film is deliberately ambiguous in many ways, and takes place in an unspecified time around the 1890s.

It becomes clear early on that loneliness is like a third character in this two-man show, with the cinematography aiding the feeling in classic black-and-white.

To be frank, Defoe and Pattinson’s characters don’t get along. In the rare moments the two are together, Thomas is constantly drinking, farting and berating Ephraim with old-timey sailor remarks.

While Defoe tends to the lighthouse, Pattinson does the dirty work of replacing fuel, fixing roofs and hauling rocks, all while being attacked by the seagulls inhabiting the island.

Among building tension the question lingers, what exactly does Defoe do while tending to the light alone all the time? Is Pattinson just dreaming of mermaids, or seeing them in real life?

“The Lighthouse,” like Eggers’ first film, “The Witch,” doesn’t quite fit into the genre of horror and lacks the classic conventions [jump scares, fast plots, the last girl trope]. By lacking a specific genre, you question throughout if it’s fantasy, horror or thriller and get dragged deeper into the world the film presents.

Eggers and Cinematographer Jarin Blaschke carefully mold the slow-burning plot, throwing in some great dark comedy, alongside dialogue accurate to the period.

Staying true to the time and focus on detail, the film is shot in 35mm film and uses a square ratio, providing an interesting art-house feel.

Blaschke was gifted two old lenses for the film, one from 1912 and the other from 1930, both modified to work with modern cameras.

Though Eggers said he didn’t intend for his film to have strong modern themes, many viewers have noticed themes of toxic masculinity and the phallus. At one point we see Thomas and Ephriam almost kiss after some drunken slow dancing, immediately proceeding to beat each other to a pulp.

As for the theme of the phallus, as if the phallic figure of a lighthouse couldn’t stand alone, we also see Ephraim masturbating, Thomas masturbating and some horror-infused mermaid sex.

Moments like these both reinforce the theme of toxic masculinity and push us to unpack the power struggles that come with leaving two men alone during a never-ending storm.

In all, “The Lighthouse” is an impressive second film from Eggers. His films have not adhered to the horror genre, creating their own rules for the audience to follow. It’s exciting and a little bit daring.

If his next films hold any similarity, you won’t leave feeling warm and fuzzy but will walk away feeling confused as to why you liked it so much.